I chose to participate in the twitter chat again because I had a good time last time, and I enjoyed the social aspects of the learning that the activity emphasized, with the constructivist and connectivist aspects being quite a big draw. Here are my responses to the questions that I participated in for the twitter chat for the 5th module:

Q1: How has technology changed education in your lifetime?

A1 For the most part, it has changed the way that I am able to supplement my formal learning through sources online, as well as facilitated a change in the way that formal education has been delivered to me, i.e. moving from in person lectures to prerecorded video. These changes have their pros and cons, as I (the learner) am more able to select what pace I want to do my learning at, and from whom/how I will learn, but it can certainly lack the personal touch that interacting face to face with the educators can have.

Q2: Continuing on the theme of technology… How will technology shape education into the future?

A2 I think technology will continue to empower distance learning to teach more learners and cover more subjects, and there is potential for new innovative methods of education that can only be achieved through the use of modern technology like MOOCs, however I think that if we continue to allow markets and tech conglomerates to decide what good education looks like, we’ll end up in a situation where learners are treated as an object to be used for profit, as consumers or as commodities to be traded, ie their personal data.

Q3: Who do you think controls the future of education?

A3 As much as I would like to say that it’s the learners, I feel like in our society we have organized so that education’s place in the world is more controlled by business; many people I know have selected their majors/degrees based on what makes them most “hireable” while there are some amazing people are resources that are available for free, most institutions/EdTech corps. are still trying to run a business, so they will cater towards the demand from both learners and businesses for education that makes a person “hireable.”

Q4 is a follow-up to Q3: Who do you think SHOULD control the future of education? Why?

A4 A joint effort from both learners and educators, with the learners advocating for their needs/wants out of the learning experience, and the educator shaping the pedagogy to meet those needs; an ongoing process throughout the learning experience unique to each experience, with edtech developed with the express purpose of facilitating that shaping of the experience, rather than supplanting the process entirely; it would be made only to be used as a tool for the people involved, even if the experience is autodidactic

Q5 asks us to reflect on the negative possibilites. What should be our biggest fear or concern with possible/plausible futures for education based on emerging trends/technologies/models?

A5 The worst that could happen is the streamlining of education as a pipeline for the commodification/alienation of the learner, a curious kid goes in, and a “perfect worker” comes out; systematic shaping of learners into cogs to produce profit for their future employers

Q6 : How do we avoid the futures we fear in education?

A6 Put more power in the hands of the learners to control how they learn, set livable minimum wages so people aren’t forced to pick their education based on their careers, and encourage an approach of lifelong learning, so learning doesn’t conclude after university/hs

Q7 : Let’s reconsider the future with a hopeful lens hope. What would an ideal educational system look like in the future? Consider any aspect of education that you think is important for the future.

A7 I’m partial to constructivist/connectivist models as I think that knowledge comes about socially, and that all of us should be able to participate in that process. A system focused on learner autonomy and free participation is something that I would be excited to see furthermore, that system should be actively made as accessible as possible, making use of technology as an enabling (rather than oppressing) tool, with its use and development being socially guided and funded.

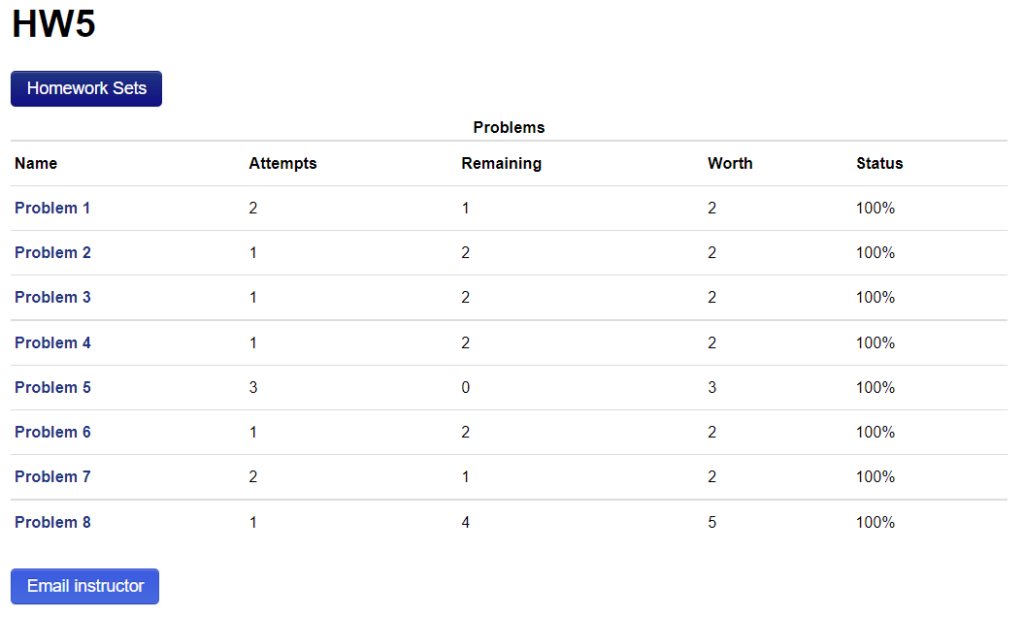

Q8: Using a GIF or an image, end with a visual explaining what you think the future will hold for education (good or bad). Remember to include alt text!

A8 //screenshot of an online math assignment. I did well, but still felt it was frustrating and convoluted due to its machine-made nature. It left me feeling more like I was being tested on if I could rotely apply the techniques from the textbook rather than understand the concepts.

I feel like most of my responses speak for themselves, but I will expand upon some of them, as well as some interesting interactions that I had with my peers that I want to reflect on in the upcoming section.

I had an interaction that I found to be interesting regarding plagiarism. A peer mentioned technology’s ability to enable students’ plagiarism, which they were asked to expand on about what motivates students to plagiarize. They went on to say that it was mostly time constraints, disinterest, and general ease of access to the process of plagiarism that lead to its occurrence. I thought that this analysis was missing a crucial aspect of the socioeconomic factor in students cheating. A student might cheat so that they could maintain a grade due to social pressure or to keep a scholarship, despite having adequate time and interest. While what my peer wrote regarding academic dishonesty is certainly true, it is also a matter of fact that in our world, grades do matter, and so unless we are able to de-emphasize the grade, we continue to externally incentivise cheating.

Another interesting interaction that I had was regarding the role that parents/guardians should play in regards to determining their dependants’ education. My peer expressed a desire to have parents play a role in shaping the education process for their child, which is something that I disagree with. It may be a personal bias of mine, but I have seen parents project their beliefs onto their children in educational settings in a way which is likely to harm them in the future. Namely, growing up in Alberta, parents are able to pull their children out of the sex ed classes in elementary/middle school, without being required to actually supplement that education in any way. According to Action Canada for Sexual Health Rights, without receiving adequate sex ed, youth are put at additional risk of pregnancy, disease, intimate partner violence, and other obviously bad outcomes (read more here.) As such, while I can understand the reasons why some may believe that parents ought to have influence in their child’s education, in practice I have seen it go wrong. Also, axiomatically, I believe that it is not a good thing for one individual to have that level of control over what another individual can learn, whether they be strangers or parent-child.

Overall, I had a lot of fun in the twitter chat, and would love to see more activities like this in my future classes. I was able to reflect more on what I think the future of education would look like, as well as what I want it to look like, which helped to shape my speculative futures assignment later on. As such, many of the ideas that I ended up considering during this chat made their way into my speculative futures assignment. A list of the readings that I was considering over the course of the chat can be found below.

References:

Action Canada for Sexual Health Rights (2019). Sex-ed: Preventing violence and increasing safety. Sexual Health Information Hub

Gilliard, C. (2016). Digital Redlining, Access, and Privacy. https://www.commonsense.org/education/articles/digital-redlining-access-and-privacy

Morris, S. & Stommel, J. (2017) A Guide for Resisting Edtech: the Case against Turnitin. Hybrid Pedagogy. https://hybridpedagogy.org/resisting-edtech/

Regan, P. & Jesse, J. (2019). Ethical challenges of edtech, big data and personalized learning: Twenty-first century student sorting and tracking. Ethics and Information Technology, 21(3), 167-179. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10676-018-9492-2

Selwyn, N., Hillman, T., Eynon, R., Ferreira, G., Knox, J., Macgilchrist, F., & Sancho-Gil, J. M. (2019). What’s next for Ed-Tech? Critical hopes and concerns for the 2020s. Learning, Media and Technology, 1–6. https://edtechuvic.ca/edci339/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2020/03/What-s-next-for-Ed-Tech-Critical-hopes-and-concerns-for-the-2020s.pdf

Rheingold, H. (2014) “Technology 101: What Do We Need To Know About The Future We’re Creating?” from Critical Digital Pedagogy https://cdpcollection.pressbooks.com/chapter/technology-101-what-do-we-need-to-know-about-the-future-were-creating/

Watters, A. (2014) “The Future of Ed Tech is a Reclamation Project” in The Monsters of Education Technology. https://s3.amazonaws.com/audreywatters/the-monsters-of-education-technology.pdf

Krutka, G., Caines, A., Heath, K., Willet, K. (2021) “Black Mirror Pedagogy: Dystopian Stories for Technoskeptical Imaginations” from The Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/black-mirror-pedagogy-dystopian-stories-for-technoskeptical-imaginations/

Recent Comments